Turning Gods Into Superheroes | Tales Of The Orishas & Hugo Canuto

Last year, I visited Bahia, one of the most magical places I’ve ever been. Its capital, Salvador, is known as the blackest city outside of

Rosario Olivas Weston is a famous Peruvian author, sommelier, food expert, and professor. She has written 11 books about Peruvian cuisine, won the Spanish National Gastronomy Award, and five Gourmand World Cookbook Awards.

How do you get in touch with someone like her?

I often ask myself the same question.

It all started with an article from Paola, whom I didn’t know then, about an indigenous Peruvian technique of dehydrating potatoes for preservation. It intrigued me, and I sent her a message.

I had long wanted to interview people about the cultural importance of food and asked Paola if she had any recommendations. She directly sent me a list of famous chefs and Rosario’s number.

Wow, ok. So do I just send Olivas a message out of the blue? I guess so.

I sent Rosario a Whatsapp on a Friday, and we had this interview the Monday after. We covered Peruvian food history, writing, and how to get a $1200 wine for $30.

Why and when did Rosario Weston start writing about Peruvian food?

The truth is surprisingly unsurprising.

Rosario’s dad was a journalist, and her mum specialized in antique books and was the head of the investigation department at the National Library of Peru. At home, they had an impressive library full of old books.

Olivas developed a love for reading early on, which was only strengthened by her parent’s friends, who also shared a passion for books, history, and investigation. Then reading turned into writing.

But what do you write about when starting out?

She considered tourism, music, and lost cities like Camino al Paititi and Laguna Cuadrada but couldn’t make up her mind. Then one day, a friend said as she was preparing dinner, “You cook well. Why don’t you write about that?”

And here we are, eleven books later.

But before we dive into Rosario Olivas’ career, let’s start with a short history of Peruvian food.

For Peruvians, food is more than breakfast, lunch, and dinner. Peruvian food is also a financial tool. Peruvians use food as insurance when prices increase rapidly.

In 1988, consumer prices increased rapidly and hit an all-time high of 7481% in 1990. Yes, that was the actual number.

Bread could triple overnight, and “investing” in food was an essential survival strategy.

In the 90s, the economy started improving. This trend continued until the pandemic.

The economy improved, and so did other sectors. Peru went from 500,000 tourists annually to 4 million in 2017 and got more exposure. More money was available for music, art, tourism, and food.

Why Peruvian food is so famous nowadays has a lot to do with these economic improvements.

Rosario Olivas Weston has been a witness and protagonist in this journey.

Did you know that the Andean highlands are home to 4,000 types of potatoes?

There are 17 megadiverse countries in the world. These countries harbor the majority of earth’s species. Out of these 17, Peru is arguably one of the most diverse.

According to the Peruvian Ministry of Environment, Peru has 38 different microclimates. You can also divide the different climates per height. Chile has 3 height climates, Ecuador has 5, and Peru has 8.

The point I’m trying to make is that Peru has one of the most varied climates in the world and, as a result, an astonishing amount of food and dishes. It’s incredibly nutritious and full of cultural importance.

The Incas, who covered six countries in today’s world, have thousands of years of knowledge. They traded across regions and enhanced the food culture.

Later, in the 80s, many Peruvians were displaced due to terrorist attacks and fled to the big cities to get jobs. They brought their food knowledge with them, which led to the fusion of recipes and new dishes gaining popularity.

In my interview with Colombian artist Andrés Ribón, he said, “we need the whole ecosystem.”

Rosario Olivas Weston told me the same. “We usually contribute the success of a dish to the chef who made it, but we need the whole system. The farmers are the ones that can tell you everything about the food. He can tell you how to grow potatoes and the differences in flavor, sweetness, and texture. Chefs rely on this Indigenous knowledge, the knowledge from the immigrants who moved to the city, and hundreds of years of cultural legacy to create the dish you’re eating today in a Peruvian restaurant.”

But there’s more to this history. For that, we need to travel back to 1925.

In 1925, Peru became home to the NGO “Bien del Hogar,” funded by Lucie Rynning de Antúnez de Mayolo. The NGO started a school focused on teaching women how to cook to provide them with a dignified life.

This school had two types of professors: the ones giving the regular classes and the special lecturers. The latter category were often famous people such as internationally acclaimed teachers and chefs.

One of these exceptional teachers was Carlota Oliart. Carlota came from a wealthy family that owned an important textile company since the 16th century.

The interesting thing about this business is that it was female-led. This was uncommon during a time when men typically ran those businesses. The ladies turned the business into one of the biggest textile companies in the country until the military regime took it in the 90s.

The generation in charge instead decided to focus on cooking. That is why when TV cooking shows started, The TV channel asked Carlota to present them, but she wasn’t interested. Instead, she suggested her daughter, Teresa Ocampo do it.

Theresa, now 91 years, became one of Peru’s most influential females. The entire Peruvian population loves her, and she had a crucial role in promoting Peruvian cuisine.

Women like Teresa and her mother laid the foundation for TV chefs who came later. The most famous among them is Gaston Acurio.

Many Peruvians and non-Peruvians only know one Peruvian chef: Gaston Acurio. I’ll explain why.

Gaston Acurio was one of the first Peruvians to study at Cordon Blue in Paris. Cordon Blue is one of the world’s most famous and prestigious culinary and gastronomy schools, with influential alumni like Yotam Ottolenghi.

Acurio met his German wife there and moved back to Peru in 1993 to open their restaurant, Astrid & Gastón, in Lima.

European chefs and cuisine had a high status in Peru, so when Gastón and his European wife opened a French restaurant, it got a lot of attention. Getting all the right European ingredients was difficult, so Acurio started focusing more on Peruvian cuisine.

In 2002, Acurio wrote his first book “Perú Una Aventura Culinaria.” In the same year, he started his first TV show on national television.

For his show, he visited restaurants all around the country. These restaurants were not only the most important ones but also included small restaurants called huariques. Peruvians call any place with good food for a reasonable price in a living room atmosphere a huarique. If you know the Netflix series Streetfood, you can probably predict what happened next. Many people went to try out these restaurants.

Because the restaurants that Gaston Acurio visited could get instant fame, the world started to believe that everything Acurio touched would turn gold.

Although Acurio’s restaurants, food quality, and innovation were the basis of his success – he won the best restaurant in Peru in 2008 and 2010 with his wife and later ranked as one of the best restaurants in the world – his TV career was probably the primary accelerator for his fame.

Gaston’s presented the TV show for 20 years and started opening restaurants in other countries. He wrote several books and built an imperium.

I like the saying, “we stand on the shoulders of giants.” Everything we create was made possible by those before us.

Rosario Olivas began publishing her books in the 90s. Many journalists and chefs have used her books containing historical information about Peruvian cuisine. Gaston Acurio, who started his first TV show in 2003, is one of those chefs. The many books and articles Rosario Olivas published became part of the basis for his TV shows.

But that’s only one side of the story. The other part is that Rosario loves doing research. She knows more than anyone I know and remembers the dates of all the important historical events.

In Olivas’ words: “Doing research is like being Sherlock Holmes. I want to get to the bottom of things.”

Her research skills came in handy. Before writing her first book, Rosario spent three years doing the groundwork for her first book.

As a professor, Rosario always tells her students to create something new. An advice she’s been following herself as well, which explains the uniqueness and niche of her first book about sweets and liquors from her family city Moquegua.

The basis of her research were family cookbooks. Rosario found a total of 377 dessert recipes that spanned several generations.

The book is unique because Rosario Olivas Weston included multiple versions of each recipe instead of picking one favorite. It allows for personal preferences, and readers can travel through generations of family recipes.

She did a lot of work standardizing the measuring system, which changed over time, making it easy for the reader to recreate and experiment with age-old traditional recipes.

It got me wondering, why do recipes change in the first place?

Some recipes never change. You can think of Italian cuisine with a focus on tradition and simplicity. The cool thing about that is that you get to taste the exact same recipe as your great-grandmother used to eat in 1930.

But some recipes do change. What changes it?

Often small personal differences. Maybe you find out that if you knead the dough slightly differently, it tastes better. Or a different technique for whisking eggs will make a cake rise more in the oven.

These changes are incorporated into family recipe books and gradually change over generations. They’re personal preferences that gradually change a culture.

Rosario’s book shows these changes in a standardized way, making history, not something from the past but something you can experience and taste. Because of its uniqueness, the book greatly impacted the culinary world and got mentions from Eulalia Vintimilla in Ecuador, Beatriz Rosells, and Jossy Sison de La Guerra.

What’s your favorite wine? I asked her.

Many came to mind, but one, in particular, was the Torgiano Rosso Riserva DOCG “Rubesco Vigna Monticchio” 2013 from Winehouse Lungarotti.

Lungarotti is a wine house from Umbria. They’re based in the mountains, which is not necessarily the ideal setting to grow grapes. That’s why Lungarotti had to do a lot of work to get the right set-up to create the best conditions (such as soil quality and optimal sunlight). The result is that they have a lot of control over the entire process, which leads to excellent wines with consistent quality.

Lungarotti is historically known for good table wines. But they have higher ambitions. They want to raise their level and create more unique and vintage wines. The Torgiano Rosso Riserva DOCG is one of these wines.

Because they’re not established in high-class wines yet, the prices are much more affordable. Rosario furthermore mentioned that Italian (as well as German) wines tend to be much cheaper than French wines. Wines from France are the most expensive because hordes of tourists buy them.

According to Rosario, the Torgiano Rosso Riserva DOCG “Rubesco Vigna Monticchio, which costs $30, could be sold for $1200 in France. Although the 2013 wine seems to be sold out, there are many other good options on Lungarotti’s webshop.

Every region in Peru has incredible dishes. It’s too much to mention in one post. Nonetheless, Rosario shared some of her favorites.

You must try these when you visit Peru (or a Peruvian restaurant).

Generally, you can divide famous chefs into three categories: the good, the cultured, and the crazy.

Of course, these categories can overlap, but to avoid overcomplicating things, here are some.

If you happen to be in the Netherlands, consider visiting Somos Peru in the Hague, Pachamama on Wheels in Amstelveen, Peruvian Cuisine NL in Amsterdam, or Inca Mania in Delft. These are a bit more low-key.

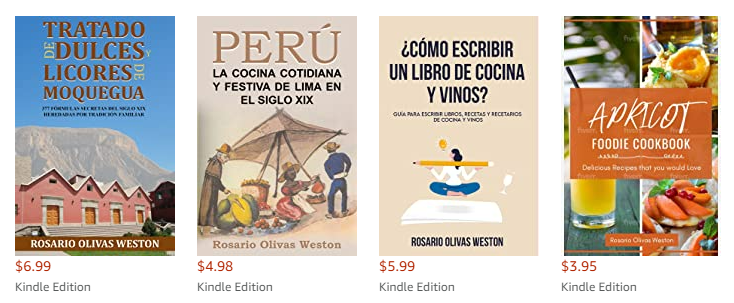

Of course, we can’t discuss book recommendations without mentioning Rosario Weston’s books.

Rosario Olivas Weston’s famous books are:

Her favorite cookbook is COOK’s Illustrated. In this book, they describe basic dishes very elaborately. For example, the book contains three pages about how to cook rice.

Her favorite movies are:

She also loves cooking programs around the world. It allows you to fantasize about far journeys and exotic foods.

You can find more interviews on the interview page.

If you want updates straight to your inbox, make sure to sign up for my newsletter below.

Every two weeks, you will receive book, music, and movie tips from countries worldwide.

Do you want global book, music, and movie recommendations straight to your inbox?

Sign up for the newsletter below!

Last year, I visited Bahia, one of the most magical places I’ve ever been. Its capital, Salvador, is known as the blackest city outside of

Ann Morgan is an author, speaker & editor. She has written four books and started two blogs, ayearofreadingwomen and ayearofreadingtheworld. She is also a Literary

I love Kenyan music and bands like Sauti Soul, but I came across something even more interesting not too long ago. I discovered the father