A Stranger’s Love

It was 4 a.m. in Paraty, Brazil. Dark, silent, almost deserted. I found myself sitting alone in the bus station, regretting that I hadn’t prepared

Last year, I visited Bahia, one of the most magical places I’ve ever been. Its capital, Salvador, is known as the blackest city outside of Africa, shaped by the millions of Africans brought to Brazil during the slave trade. Out of that history, the people of Bahia created something incredibly rich—music, food, capoeira, and Candomblé: a religion that mixes African spiritual traditions with Catholicism.

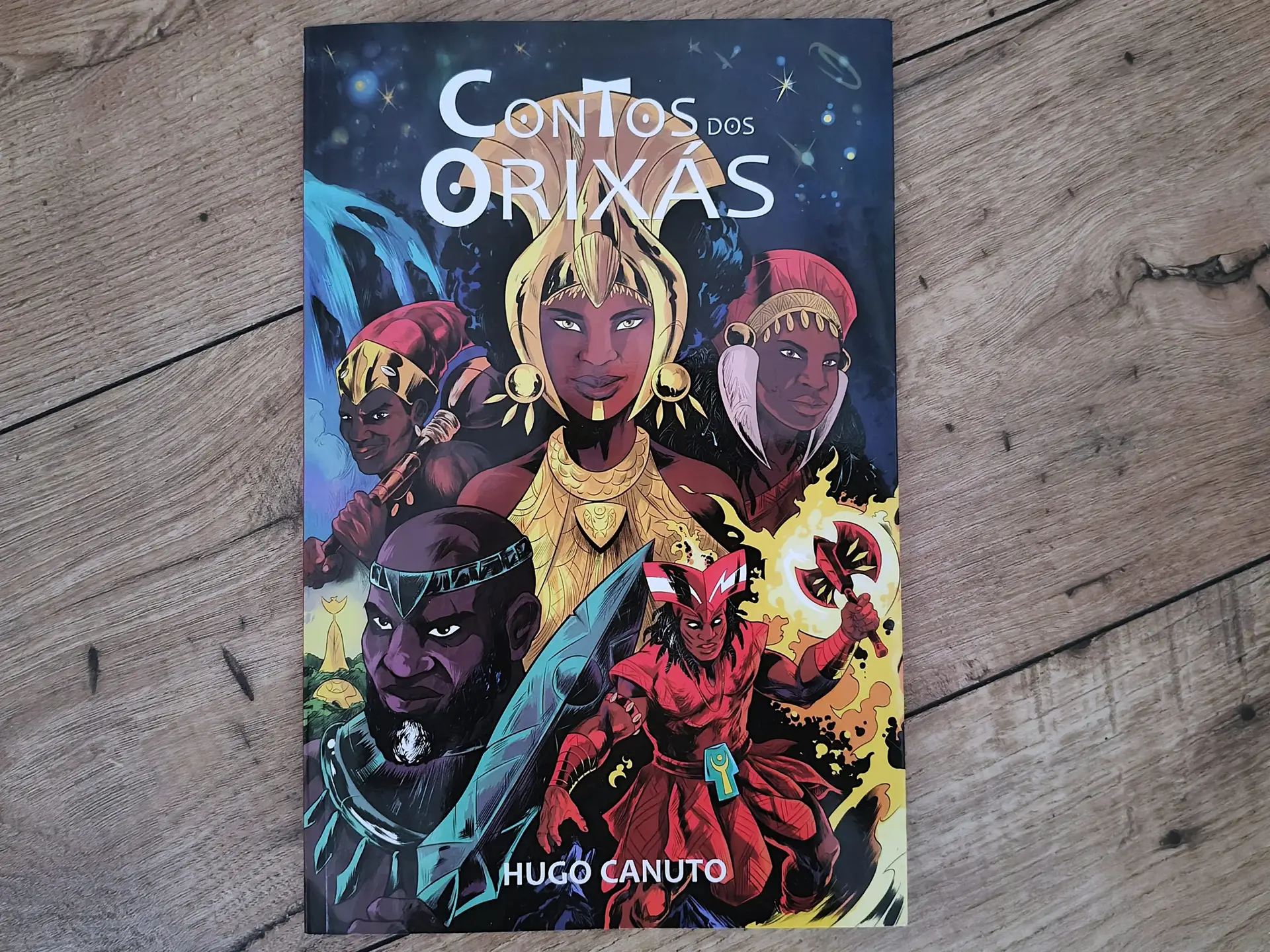

The day after attending a powerful Candomblé ceremony, I walked into a bookstore in Salvador and saw Tales of the Orishas. I bought it, started reading, and was immediately hooked. The mix of mythology, history, and comic book energy hit me right away. So I reached out to the artist: Hugo Canuto.

Hugo is a comic book artist from Bahia who reimagines the Orishas—the spiritual figures (or Gods) in Candomblé—as superheroes. His work has been featured by the Smithsonian, Carnegie Hall, and Abrams Books, and he’s won multiple awards, including the HQ Mix Prize, Brazil’s most important comic award.

In our interview we discuss Hugo Canuto’s journey, what we can learn from Candomblé, and his personal lessons. Read on!

I’ve loved comics ever since I was a kid. My first contact was with Marvel and DC—superheroes like Thor, the Fantastic Four, Conan the Barbarian, Superman, Batman.

I grew up wanting to make comics myself—but this was over 30 years ago, before the internet, and in Brazil, that dream felt very far away. Mike Deodato, for example, started working for Marvel and DC in the ‘90s. But for my generation, making comics—especially for big publishers or even in Brazil—felt almost impossible.

At the same time, I’ve always loved my culture and my land. Bahia is the Blackest state in Brazil by population, and the culture here is strong. You see Afro-Brazilian heritage everywhere—in the streets, the corners, the monuments, the food, the music, the philosophy. It’s who we are.

So, I’ve always had this drive to make comics—but comics that spoke about my culture: Bahia, Brazil, Latin America.

After reading so many books and comics shaped by Western heroes and Western heritage, I started asking myself: why aren’t we represented? Why don’t I see Brazilians, Latin Americans, or Africans in the stories I love?

That question planted a seed.

It happened 10 years ago.

In my personal life, I began visiting terreiros (worship houses) and experiencing Candomblé in Bahia more deeply. At the time, I was working at a state-owned company for urban development. There was a conflict—radical religious groups were trying to destroy a cultural heritage site in Salvador: the Stone of Xangô.

I was invited to join a working group with the Bahia state government to help protect the monument and create an urban park in that area. That’s when my connection to Candomblé and Afro-Brazilian heritage grew stronger.

Years later, when I started making comics, that experience came back to me. I felt a pull—to bring everything I had lived through into my art.

That’s when I started drawing the superheroes based on the Orishas.

The superheroes exploded online. People from Nigeria, the U.S., Brazil, Cuba started reaching out: Is this a comic book?

Teachers from elementary schools in Brazil wrote to me, saying, You need to make this into a comic. Because of religious intolerance, it was hard for them to talk about the Orishas or African heritage in the classroom. Things have improved a bit since then—but back then, it was a real struggle.

So I decided to make the comics—both as a way to strengthen a culture that’s vital to Bahia and Brazil, and to stand against the forces trying to erase it.

When I decided to start, the first thing I did was visit the Terreiro of Afonjá in Salvador. I had an appointment with Mãe Stella who was still alive then.

I told Mãe Stella that I had started making this art and that I wanted to contribute to this heritage through my comics.

She listened kindly and simply said, Do it. When it’s ready, bring it to us.

So I began with Tales of the Orishas.

The second thing I did was find a teacher—Professor Adelson de Brito, a Yoruba scholar in Salvador. I started taking Yoruba classes with him, and he became my guide—my mentor and consultant on the project.

Unlike Greek myths, the stories of the Orishas belong to a living religion—practiced by millions across Brazil, Cuba, Latin America, and Africa. These aren’t ancient rituals from a distant past—they’re alive. So I knew I had to approach them with care, respect, and intention.

The first challenge was how to adapt the myths. In Nigeria, the traditions differ from Brazil. For example: in Yorubaland, Yemayá is the Orisha of the river Ogun. In Brazil, Iemanjá becomes the goddess of the sea. Or how in Brazil, Xangô, Ogum, Exu, and Ossain are often seen as closely related or symbolic brothers—while in West Africa, they belong to different regions and lineages.

So I had to choose. I built my own fictional continuity in Tales of the Orishas, rooted in specific traditions, and shaped the mythology into a graphic novel. That became the foundation.

As I researched, I went deeper. I studied the Oyo Empire and discovered why rituals and foods like acarajé are so tied to Salvador. The word comes from Yoruba: akara means “fireball,” and jẹ means “to eat.”

In total, I spent two years studying and creating Tales of the Orishas, making sure not to copy directly from any terreiro—no exact symbols, no borrowed costumes or tools. I recreated everything from scratch.

Every color, every design—infused with the spirit of the stories, but drawn in the comic book style I grew up with… especially Jack Kirby.

And then—

The whole process of making the first comic took about two years. I funded Tales of the Orishas through crowdfunding, which is a very efficient way for me to produce my work as an independent comic book author in Brazil.

In the beginning, some people were resistant—mostly because it was something different, something they hadn’t really seen before. But overall, people loved it. In the terreiros, in schools, among students, worshippers and non-worshippers of the Orishas, even in the university art world—the work was deeply appreciated.

I think the Tales of the Orishas opened up space. After that, many other authors in Brazil started exploring comics about the Orishas without fear—without worrying so much about prejudice or retaliation.

And the criticism? I never gave it much attention. I don’t spend time reading Facebook or Instagram comments. My philosophy is simple: on my pages, if someone starts to offend or argue, I block them. On other profiles, I don’t care—it’s not my space. If someone says they don’t like the work, that’s fine. As long as it’s not personal, I move on.

I read more than 40 books, and still, it’s just the shore of the ocean. Candomblé is a living tradition that speaks about family, ancestry, ecological thinking—about nature and humanity as one.

At first, some might think Candomblé is only about the past, because it honors ancestors and the Orishas. But it actually holds incredibly contemporary ideas—ideas that speak to the world we live in now.

I’d even say that Candomblé, as an African traditional philosophy, carries a spirit of life that can offer an alternative—and even healing—to our Western culture of death: consumerism, environmental destruction, extremism, militarism, all these suicidal behaviors that continue to shape our society.

Candomblé is a philosophy deeply integrated with nature. Humans and gods are part of it. The gods are nature. Olodumare, the creator, and the Orishas are all expressions of nature itself. It’s a beautiful way of thinking.

It reminds me of Japanese Shintoism in some ways—another tradition that connects divinity and nature. Not to make direct comparisons, but the feeling is similar.

It helps us live in the world, stay connected to ourselves—and maybe, even helps us find answers for the future.

Regarding nature, it’s an integrated mindset. We treat a tree as a whole, living being, just as we are. Science confirms this—trees are living beings.

But in Western societies—and often in Eastern ones too—we’re taught to treat nature like a box of resources: mine it, cut it, take from it until there’s nothing left. This leads to destruction, pollution, and unregulated industrialization.

Candomblé, along with other African traditional teachings, shows us another way: to see nature and the planet as a living whole that must be preserved. I truly believe this perspective offers powerful answers for how we can evolve our relationship with the natural world.

The way Candomblé looks at death, we believe that life does end with the body. ⁓ We believe that some people become ancestors, men and women, reincarnation, to go back to the…land and family after some time. That is a transitory state for our spiritual balance.

There’s a book I always recommend. It’s the catalogue of an exhibition that took place at the Fowler Museum in California a few years ago. It’s called Axé Bahia.

The book is a rich catalogue that tells the story of Afro-Bahian arts—from the colonial period up to around 2018. It covers everything: our music, our artists, our monuments, our spiritual life, our culture.

It was a beautiful exhibition. And interestingly—it never happened in Brazil. It happened in the U.S. Sometimes, it feels like other countries treat our culture with more care than we do ourselves. But the museum did an incredible job.

The catalogue is full of photos. It’s beautifully done. I always tell my foreign friends to get it, because it gives a full perspective on Brazilian culture from Bahia.

The research is deep. Brazilian scholars and curators worked on it, and it includes everything—arts, sculptures, food, music, the spiritual traditions. It’s amazing. I always recommend this book.

Wow—I’ve done over 20 trips and events in just the past 12 months. It gave me a completely different perspective on Brazil. I’m privileged to say I’ve been to 21 of Brazil’s 27 states. Last year alone, I visited the Amazon three times—each time in a different region or capital.

I also traveled to French Guiana, Angola, Portugal—and now I’m heading to Germany for a week at Bayreuth University for a congress. Each place reveals something new.

These experiences expanded my view—not just of Brazil, but of the Global South. I’ve gained a deeper understanding of how different countries relate to political systems, economic structures, and the lingering effects of colonialism. It hasn’t disappeared—it’s just taken new forms.

As an artist, it makes me more curious. I believe that travel—when you connect with other cultures and stay open—makes you more humble. And wiser.

Man, I really hope to see this deep, monstrous, and barbaric inequality that shaped Brazilian society finally disappear—or at least shrink. It consumes our lives. Living in a society so defined by hierarchy—those who have and those who don’t—is exhausting. Everything is divided.

You see it in the urban landscape: people in favelas, and others in four-bedroom apartments facing the sea. It’s impossible to build a country like that. It’s like an open wound—something that must be healed. There’s no culture, no peace, no real prosperity where inequality runs that deep.

And sadly, I’ve seen this in other parts of the world too. Even in the U.S. or Western Europe, inequality is rising. We need to reflect on that. It’s not about having wealth—it’s about how we share it. The U.S. is the richest country in the world, yet people live in trailers. Brazil is heading down that same road.

So when I’m old, I hope things are better—for everyone. That we’ve democratized access to culture, to books, to good food, to joy. That’s what I really wish for the future.

Hugo Canuto recently gave a talk at Carnegie Hall alongside writer Ytasha Womack and scholar John Jennings, where they discussed the creative process behind The Tales of Orishas and the wider world of Afrofuturism. You can find it on YouTube.

The first volume of Tales of the Orishas is available in English through Abrams Books. The second volume is already finished and translated—Hugo’s just waiting on the green light from his publisher. Fingers crossed it will be out soon.

Hugo hopes to spend more time in the U.S. in the future, connecting with readers, artists, and communities—especially among Brazilians, African Americans, Cubans, and anyone drawn to this cultural world.

As Hugo Canuto says: “It’s important for me to open these doors in the English-speaking world—to share our artwork, and to show the Brazilian contribution to global culture.”

Do you want global book, music, and movie recommendations and interviews like this one with Hugo Canuto straight to your inbox?

Sign up for the newsletter below!

It was 4 a.m. in Paraty, Brazil. Dark, silent, almost deserted. I found myself sitting alone in the bus station, regretting that I hadn’t prepared

“Bahia Days Are Like Holidays,” – Captains of the Sand by Jorge Amado. Sometimes, for some unexplainable reason, you feel connected to a city even

There are many interesting aspects that generally everybody knows. For example, Brazil is seventh most populous and fifth-largest country by area of planet Earth. It