Turning Gods Into Superheroes | Tales Of The Orishas & Hugo Canuto

Last year, I visited Bahia, one of the most magical places I’ve ever been. Its capital, Salvador, is known as the blackest city outside of

Welcome to a new interview with Ethiopian artist Mezgebu Tesema.

Mezgebu Tesema is a contemporary Ethiopian painter recognized for his captivating and lifelike paintings reflecting Ethiopia’s rural livelihood.

Born in the small town of Enewari, Mezgebu’s upbringing in the central highlands of Ethiopia greatly influenced his artistic consciousness and imagination. His work is closely associated with rural Ethiopia, and his contribution to depicting their beauty shows in his career.

Mezgebu Tesema belongs to a group of well-known artists in Ethiopia, including Behailu Bezabih and Bekele Mekonnen, who studied similar disciplines during the Dergue era.

The influences during this era, his time living in Russia, and his childhood memories converted into a unique and stunning artwork collection.

For the previous 30+ years, Mezgebu has also been a professor at the Ale School of Fine Arts and Design in Ethiopia, where he brought Ethiopian art to new heights. He sees himself as part of a rich tradition of painting rather than a pioneer of a new movement and has shaped artists such as Petros Meaza and Fitsum Tefera, who became renowned painters in America.

At first glance, Mezgebu gives the impression of a humble and wise artist who chooses his words carefully. Then, as you start talking to him, it quickly becomes apparent that he has a great sense of humor and a neverending passion for art and life.

I’m therefore very excited to share my interview with Mezgebu Tesema, full of insights into Ethiopian culture.

The major inspiration source for me is my childhood life, not because I grew up in the countryside but the situation when I grew up in the countryside.

You spend most of your time in outdoor activities, observing things that allow you to see and observe how they interact.

At the same time, you’re allowed to fantasize about different kinds of thoughts. It was the most comfortable atmosphere for you to be with your thoughts and memory.

In those days, there was no right and wrong; you decide what you want to do and give your personal meaning to things. Maybe these meanings are not shared by your friends, but they matter to you and remain in your memory all the time. That’s a very important source of inspiration for me.

When you are a child, life’s an adventure for you. You stand at the edge of the gorge and are fearless. It’s your achievement as a small human being. That long-standing self-approval still exists in my mind.

Whatever you do, there is a certain amount of ideas, feelings, and memories you share with other country people. There is a collective memory that you share with other people, which helps you to communicate.

At the same time, every spectator, every participant observing your work, interprets your work according to the spectator’s experience. As you know, painting tends to be metaphoric, and it has multiple meanings, and you can’t control those meanings. It’s participatory as you share the images with others.

You have to expect different meanings from everyone in your artwork. That’s the nature of the art itself.

Let me give you a paradox.

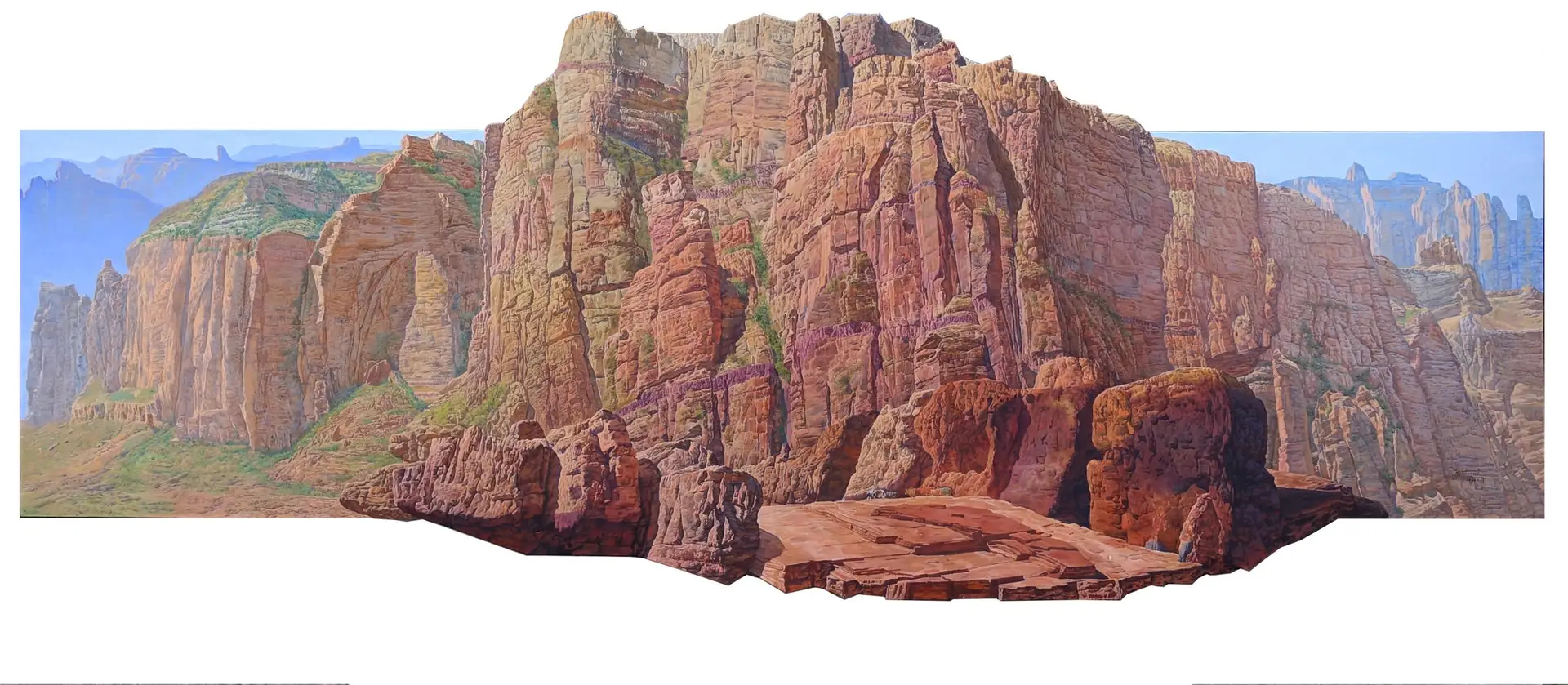

There is one painting titled “The Heat.”

From my childhood experience, charcoal is used to cook food in the countryside and to make the room warmer during summertime. For you, it’s summer, but for us, it’s cold weather. It’s another paradox. When I say summer, it’s cold in the Ethiopian context.

And that one moment is big in my mind. When the idea is occupied in your mind, it’s big, even though the actual object (the charcoal) is small.

I made that wooden charcoal very large and out of context, out of its proportion. When it was displayed, I tried to explain the heat, the one aspect of the fire.

Similarly, there is a popular place, in our mainland area, in the north of Ethiopia, called Erta Ale. There are active volcanoes there. And it’s very popular because many times it’s displayed in the television and journals of communications. And because of the size of the canvas, almost everyone associated the painting with Erta Ale.

Erta Ake is also, I think, the warmest place in Ethiopia. I’m talking about the heat, the warmth of the fire. Although the interpretation is different, we understand each other through these different ideas or understandings.

As an artist, I believe that the painting has its own life related to its application or organization or the way you present your work.

I give a great emphasis on that, really, as the outcome is always subjective. It’s uncontrollable. If I give attention to controlling the perception, the formal aspect of the artwork will suffer a lot. That is my stand when I’m working on my artwork.

Of course, there are many situations in society, bad and pleasant. For me, the positive aspect of the artwork is very important, especially if somebody is living in a bad situation, as art is the remedy for bad times.

I’m always trying to work on positive ideas. I guess not in a verbal aspect of meaning but in the sense of adding positive meaning or feeling. That’s my dream.

It also relates to my childhood feeling because my childhood life is precious and important to me. And I’m always trying to reflect that positive idea.

I was actually one of the active participants in the celebration when I was a kid. You can imagine having that colorful dress code and running around with your friends. Coming from a small town, it was a great image, a good monument to observe. And you prepare for a long time to participate in that celebratory activity.

It has been a big memory, and my dream was to make a large-size painting.

For me it’s a good topic, working on that celebration. I think that memory wanted to make me that image.

You know, Adbar as an idea developed by narration.

When I was a kid, my parents and people in the neighborhood told us stories about Adbar. But Adbar doesn’t have any image. And those narrations helped me to fantasize about the images of that Adbar. The narration was so positive that you love Adbar without knowing her and it also gives you a little freedom to depict her in your own way.

You know, Adbar plays a role in protection. And if you’re Christian, Jesus feels like that protective spirit.

The Greek mythologies have images made by the Greeks. The Christians have an image made by traditional artists and European artists. Other belief systems already have established images that we collectively share with other people.

The images created by these artists are helpful to have a common understanding, but our personal relationship with God is different and more like that of a protective spirit. In that way, the Adbar spirit has a similar condition to how many others imagine their creator or protector.

Yeah, yeah, yeah. Of course. As far as you are dealing with the imaginative aspect of the world, the pushing energy that exists with your thoughts is not visible.

Sometimes it’s difficult to define, and you want to share it with other people despite the limitation of language.

That aspect of energy, inspiration, and communication is related to the spirit in my belief.

Frankly speaking, I don’t have a problem selecting themes or working on a certain idea.

The only difficult thing for me is that I am a slow maker. In the academy, my strongest aspect of making paintings was organizing the composition, but it was also the hardest part, and it slowed me down.

I don’t always like that aspect of me.

If needed, I force myself to finish it. I know it’s painful, but I have to accomplish that.

Other times, I don’t have strict rules. I start different paintings at the same time. And through time, when I work on one painting, I understand the other. When working continuously on one painting, you get tired and transfer to the other one. And then, through the process of making another project, you accomplish the first.

Another strategy of mine is that I look at my work as a separate project. I’m not trying to connect one work with the other, and I’m not focusing on a certain amount of income.

I’m practicing what I believe and focus on what I want to work on. That is my strategy.

I spent 7 years in Russia. The 1st year was a language school, and the other six years, I studied art education.

Frankly speaking, I was looking for scholarships for higher studies abroad, and scholarships were available in Russia and other Eastern European countries. Also, some instructors were already studying in Russia to study realistic or figurative drawings and paintings, and they used to share how the academics work, the education system, and the institutes’ culture. We were also eager to study abroad.

Of course, when you travel from Africa to Europe, it’s completely another dimension. Everything is new. The first time you get disoriented, and you need help. Also, I didn’t know a single word about the Russian language, so it wasn’t easy to communicate.

After the preparatory class at the Russian Language Institute, I could communicate with people. Then I started to understand the culture and tried to catch up with the education.

I also remember that Russian students were very helpful, and they were always open to me, and I learned a lot from them. The professors also understood where I came from, and frankly speaking, I had a pleasant time in Russia.

Yes, you know the first thing I… I missed…home, you know, the landscape and everything. Also, imagine a person from Africa surrounded by white people.

Sometimes I felt that I changed my color. Sometimes you feel you are a white person because you don’t see any black people. I also had never seen snow falling.

And then, when I joined the institution, the language barrier was intense. I mean, really difficult, especially in the first two years, attending lectures and reading books.

The education methodology was so strict, and you had to be disciplined. This kind of discipline I had never experienced before, and the demand from the students was very high.

It was so academic, so instead of allowing you to be creative, they taught you what had been discovered in the classical period. There were sequential courses from the first year up to the fifth year, and until you started your graduation work in your last year, you were discouraged from doing things differently.

Yes, yes, yeah, yeah. The world was different after we arrived as there was a Cold War and a West and East block.

When I returned, things were different. I got the opportunity to read Western books and later also had a chance to visit the United States. All these periodical changes allowed me to change my mind and practice different ways of giving education to students.

When I say changing my mind, it doesn’t mean it’s revolutionary. It’s a kind of evolution that helps you to continue what you have and, at the same time, add something new onto that.

Especially in material knowledge, my drawing skills, understanding of relationships, and figurative organizations developed highly. I had changed, and as I got older, I felt more responsible for my art.

Also, you know, when you arrive, you face new and different problems.

Strict academic subjects were difficult relative to our culture, and school resources were limited. Some things are not available to continue with the academic way of giving lessons.

We had shortages of art material, space, and sometimes difficult situations when communicating with colleagues.

When you have studied abroad for seven years, you know, you learn different approaches and ideas, and when you try to transfer that knowledge, the understanding is not always that simple, really.

Self-expression is very important, and it’s not always easy in African countries, not only in Ethiopia.

When I say self-expression, I’m not only talking about the political and cultural influence of the country or the economic aspects of the country. Self-expression is how you transfer and convey what you want to express through your artwork. It is a challenge to express yourself, as I have seen students struggle to identify what they want.

You know, European artists have a tradition of manipulating other countries’ cultures.

African artists are marginalized as tribal artists, or they are discouraged from being free like European artists. And even if you try ignoring these outside influences, that discouragement is not easy. It’s not simple to ignore.

I know some of my colleagues are living in Europe. They are expected to make the traditional (African) way of making art. Whereas European artists are free to choose whatever they like, which is unfair, in my opinion.

The paradox is that there is a law saying artists should be free. And at the same time, the offering conditions limit your freedom.

In every profession, a human being cannot survive without skill, but when it is 100% skill-based, it is also unacceptable.

For example, if you are making a painting, you have to know how to handle the materials and their characteristics. The canvas has been the same for a long period of time, and you’ll always have to deal with its traditional rectangular surface. That’s why you have to know the rectangular view of your composition first and go further based on that.

At the same time, I also advise my students to express themselves. I use my personal experience to embody an invisible feeling in a certain kind of image.

It may sound selfish, but it’s that feeling that creates a connection with society within a country or a similar culture.

When you graduate from the school. You are compromised due to different activities to support yourself through income. And students do administration or advertising work to get money.

To support your professional activities, you might take a job that you don’t like. Artists have to be tactful and flexible.

For me, discipline is very important in life. When I say discipline, I mean the whole aspect of discipline. The minor task needs a certain amount of discipline.

The other one is hard work. The hard work is supported by the discipline. It’s the most important thing I value in my life, and following this principle, I have never been disappointed in my life.

I think my kids were also learning it by observing me as they are attached to my artwork and how I emphasize my work. It gives the possibility to them to learn without verbal explanation. I would create incentives to teach them these lessons.

It’s funny; all three of my kids are so disciplined now. I can almost say they are workaholics.

It might be weird to hear about this idea. There are things that are in your mind that you can’t really express to people.

I’m so obsessed with the idea of giving an image to the imageless aspect of life.

As an example, I have one painting with the title the image of uncertainty. Or the image of being uncertain.

When I have difficulties deciding on one thing, when I feel helpless or get confused, that uncertainty is always big in my thoughts. And I’m trying to express that.

The artist which I like most in my life is Andrew Wyeth, an American artist who lived in the countryside. I also had a chance to see his original works when I was in Russia. He learned most of his skills and experience from his father, who was also an artist. So, basically an artist family. They lived in a small village called Chadds Ford and worked in those limited surroundings (he was a regionalist of often said “I paint my own life”). I like this world and the cultural moments he created.

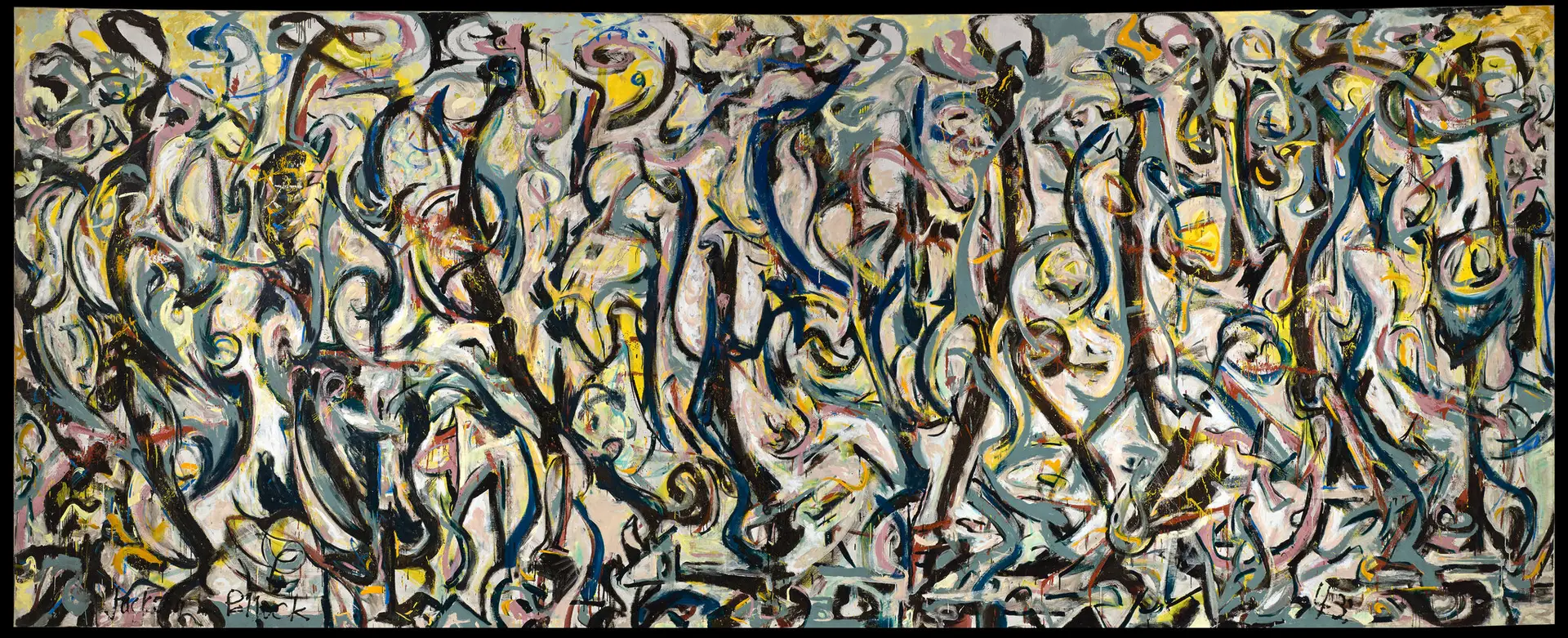

Of course, I like other artists like Jackson Pollock. Maybe the understanding of Jackson Pollock is different from others. I’m accepting Jackson Pollock as a landscape painter. It’s difficult for me to accept that his paintings are abstract. Because these random patterns exist in nature. You can find such an image in the place where I grew up. When I saw his painting, I accepted it as images I had seen before. As a figurative painter, I don’t have any barrier to communicate with his artwork.

I would say “develop yourself,” and I think I would put it in the most popular church in an Ethiopian context.

I don’t know whether it is ethical or not, and maybe my desire or motto may sound selfish in Europe or America, but the personal aspect of life is undervalued in Ethiopia.

In my country, communal things are important, and people always consider others, whether negatively or positively.

Our society is religious, which has its value, but developing one’s self is an aspect that’s often lacking.

If you liked this interview with Mezgebu Tesema about Ethiopian art and want to learn more about the country?

Check out this post about New & Old Ethiopian Music | A Top 10 Music Legends. You can also find more information on the Ethiopia country page.

For more interviews about books, music, food, and movies have a look at the interviews here. For example:

Do you want global book, music, and movie recommendations straight to your inbox?

Sign up for the newsletter below!

Last year, I visited Bahia, one of the most magical places I’ve ever been. Its capital, Salvador, is known as the blackest city outside of

Ann Morgan is an author, speaker & editor. She has written four books and started two blogs, ayearofreadingwomen and ayearofreadingtheworld. She is also a Literary

I love Kenyan music and bands like Sauti Soul, but I came across something even more interesting not too long ago. I discovered the father